According to the Theme Handbook, internationalization is defined as “the process of developing your theme, so it can easily be translated into other languages”. Accordingly, if you want to list your product in the WordPress.org Theme Directory or Plugin Directory, all text must be translatable.

When internationalizing in this sense, the key points are as follows:

- Setting the text domain appropriately

- Applying translation functions (such as

__()) to all text

However, this is internationalization in a narrow sense, and the Block Editor Handbook refers to internationalization as “the process to provide multiple language support to software, in this case WordPress”. In other words, simply setting the text domain and using translation functions may not be sufficient.

In this article, based on my experience contributing to WordPress development, I would like to introduce some of the key aspects of internationalization in the broadest sense, as well as some aspects that are often overlooked.

Translation

String Concatenation

While it is essential that all text is translatable, there may be cases where some text changes dynamically, for example.

// ❌ Don't

const fieldName = getFieldName();

const errorMessage = __( 'There is invalid text in the ', 'my-plugin' ) + fieldName + __( 'field.', 'my-plugin' );This is a very bad example because, from a grammatical perspective, it fixes the order of the text. Because the order of subjects, verbs, and objects varies between languages, your implementation must accommodate this, even if some of the text is dynamic.

In WordPress, the recommended approach to address this issue is to use placeholders. You should also add Translator comments to provide translators with context about dynamic elements.

✅ Do

const fieldName = getFieldName();

const errorMessage = sprintf(

// translators: %s: field name.

__( 'Invalid text in %s field.', 'my-plugin' ),

fieldName

);Another unusual example of string concatenation causing problems is the “percentage” string in the Gutenberg project.

// ❌ Don't

function Test( percentage ) {

return <p>{ `${ percentage }%` }</p>;

}Surprisingly, the percent signs can be swapped or even changed depending on the locale, so string concatenation should be avoided here as well. There’s no meaningful text in the translation strings, so a translator’s comment would also be a good idea.

// ✅ Do

import { __, sprintf } from '@wordpress/i18n';

function Test( percentage ) {

return (

<p>

{ sprintf(

/* translators: %d: Percentage value. */

__( '%d%%', 'my-plugin' ),

percentage

) }

</p>

);

}Link Internationalization

Links to external resources may be embedded in the text. Depending on the external resource, it may be translated into several locales, and the URL may be different. If there is such a possibility, make the link itself translatable.

<?php

// ❌ Don't

_e( 'Please refer to <a href="https://example.com/">this handbook page</a> for more information.', 'my-plugin' );

// ✅ Do

printf(

__( 'Please refer to <a href="%s">this handbook page</a> for more information.', 'my-plugin' ),

esc_url( __( 'https://example.com/', 'my-plugin' ) )

);Note that while this format is fine in PHP, React escapes the HTML, so you need to use createInterpolateElement to convert the tag names in the string into React elements.

import { __ } from '@wordpress/i18n';

import createInterpolateElement from '@wordpress/element';

function Test() {

return (

<p>

{ createInterpolateElement(

__(

'Please refer to <a>this handbook page</a> for more information.', 'my-plugin'

),

{

a: <a href={ __( 'https://example.com/', 'my-plugin' ) } />,

}

) }

</p>

);

}Sentence Concatenation

To join two sentences together, a half-width space may be hard-coded between them.

// ❌ Don't

import { __ } from '@wordpress/i18n';

function Test() {

return (

<p>

{ __( 'It is sunny today.', 'my-plugin' ) }{ ' ' }

<strong>{ __( 'Tomorrow will be rainy.', 'my-plugin' ) }</strong>

</p>

);

}This renders in English as the following HTML (minor details omitted):

<p>It is sunny today. <strong>Tomorrow will be rainy.</strong></p>In English, this is correct because we put spaces between sentences, but what about in Japanese?

<p>今日は晴れです。 <strong>明日は雨でしょう。</strong></p>There is a space after “今日は晴れです。” In Japanese, there are no spaces between sentences, so this feels a little strange.

In cases like this, as mentioned above, in PHP, you can include the HTML tag in a single translation string. In React, use createInterpolateElement.

// ✅ Do

import { __ } from '@wordpress/i18n';

import createInterpolateElement from '@wordpress/element';

function Test() {

return (

<p>

{ createInterpolateElement(

__( 'It is sunny today. <strong>Tomorrow will be rainy.</strong>', 'my-plugin' ),

{ strong: <strong /> }

) }

</p>

);

}Conversion (word formation)

“Conversion (word formation)” is a phenomenon in which the part of speech changes without changing the form of the word. For example, imagine the following translation:

// ❌ Don't

<h2><?php _e( 'Post', 'my-plugin' ); ?></h2>

<button><?php _e( 'Post', 'my-plugin' ); ?></button >

<h2><?php _e( 'View', 'my-plugin' ); ?></h2>

<button><?php _e( 'View', 'my-plugin' ); ?></button >In English, you can determine whether a text is a noun or a verb depending on the context in which it is used. However, there are locales where different words are used for nouns and verbs, and a single word cannot cover both.

For example, in Japanese, you might want the following text:

<h2>投稿</h2>

<button>投稿する</button >

<h2>ビュー</h2>

<button>見る</button >The way to achieve this is to provide context for your translation strings.

// ✅ Do

<h2><?php _ex( 'Post', 'noun', 'my-plugin' ); ?></h2>

<button><?php _ex( 'Post', 'verb', 'my-plugin' ); ?></button>

<h2><?php _ex( 'View', 'noun', 'my-plugin' ); ?></h2>

<button><?php _ex( 'View', 'verb', 'my-plugin' ); ?></button>Another interesting example that actually occurred in the Gutenberg project is the “conversion of proper nouns and adjectives.”

<button type="button"><?php _e( 'Small', 'my-plugin' ); ?></button >

<button type="button"><?php _e( 'Medium', 'my-plugin' ); ?></button >

<button type="button"><?php _e( 'Large', 'my-plugin' ); ?></button >This might seem fine at first glance, but there is a web service called “Medium,” which is a proper noun.

In Gutenberg, context has been added to the proper noun so that “Medium” can be translated separately from “Medium” as an adjective.

// 固有名詞

<a><?php _ex( 'Medium', 'social link block variation name', 'my-plugin' ); ?></a>

// 形容詞

<button type="button"><?php _e( 'Medium', 'my-plugin' ); ?></button >Block Development

Don’t Use Translation Functions in Save Function

When developing a block, you may want to set default fallback text that can be changed and localized.

Also, if you want to save block content in the post conent, it’s common to define that information in the save function. For example, what would happen if you wrote the save function as follows:

// ❌ Don't

import { RichText, useBlockProps } from '@wordpress/block-editor';

export default function save( { attributes } ) {

const { content } = attributes;

return (

<div { ...useBlockProps.save() }>

<RichText.Content value={ content || __( 'Hello World', 'my-plugin' ) } />

</div>

);

}The intention of this code is to prioritize the text set by the user, while providing localized text as a fallback. While this code may seem fine at first glance, its implementation could cause the block to break. Imagine the following flow:

- User A has their WordPress locale set to English.

- User A inserts this block into a post and saves it.

- User B has their WordPress locale set to Japanese.

- User B opens the post posted by User A.

This is where the block breaks.

The reason for this is block validation, which checks whether the actual HTML saved in the post content matches the HTML generated by the save function, and raises an error if they don’t match. The translation function dynamically changes the text based on the user’s locale, which means it might not match the text saved in the post content.

I haven’t found an ideal approach to this yet, but one approach is to make blocks dynamic and render fallback text server-side. For example, the “next page” block (core/query-pagination-next) has translatable default text while respecting the block’s attributes.

Don’t Define Default Text in block.json

The only text in block.json that is automatically considered translatable is the fields defined in the block-i18n.json file, so defining a string as the default value for attributes like this will not make it translatable:

{

"apiVersion": 3,

"name": "my-plugin/my-block",

"title": "My Block",

"attributes": {

"content": {

"type": "string",

"source": "html",

"selector": "div",

"default": "Hello World"

}

}

}One solution is to set the default value on the server side, as explained in the previous section.

Don’t Define Content in example Field of block.json

The example field is primarily used to display a preview of the block, but as mentioned above, the string defined in this field is not translated.

{

"apiVersion": 3,

"name": "my-plugin/my-block",

"title": "My Block",

"attributes": {

"content": {

"type": "string",

"source": "html",

"selector": "div",

"default": "Hello World"

}

},

"example": {

"attributes": {

"content": "Hello World"

}

}

}The solution is to define example directly in the regisiterBlockType property, rather than in block.json.

// ✅ Do

import { __ } from '@wordpress/i18n';

import { registerBlockType } from '@wordpress/blocks';

registerBlockType( 'my-plugin/my-block', {

apiVersion: 3,

title: __( 'My Block', 'my-plugin' ),

// ...

example: {

attributes: {

content: __( 'Hello World', 'my-plugin' ),

},

},

} );RTL Languages

RTL (Right-to-Left) languages are languages in which text is written from right to left, and Arabic is a typical example. English and Japanese are LTR (Left-to-Right) languages. WordPress supports both LTR and RTL languages, so checking that your product works correctly in RTL languages is an important aspect of internationalization.

StyleSheet

WordPress provides several convenient mechanisms for adding stylesheets for RTL languages.

One of these is style.css, the theme’s main stylesheet. If you want to load completely different styles for RTL languages, create style-rtl.css and write the styles for RTL languages there.

Alternatively, you can use the wp_style_add_data() function to replace any stylesheet file.

<?php

wp_enqueue_style( 'my-theme-style', get_template_directory_uri() . '/content.css', array(), wp_get_theme()->get( 'Version' ) );

// RTL styles.

wp_style_add_data( 'my-theme-style', 'rtl', 'replace' );In this example, place the content-rtl.css file at the same level as the content.css file.

Build Tools

Creating your own stylesheets for RTL languages is difficult because you have to invert all the physical properties.

/* LTR */

margin-left: 16px;

padding-right: 8px;

left: 0;

/* RTL */

margin-right: 16px;

padding-left: 8px;

right: 0;This process wouldn’t be necessary if you standardized your code using logical properties from the start, but WordPress core, Gutenberg, and the default theme use RTLCSS (or its wrapper library) to automate this transformation.

Using it is very simple; just specify the “original CSS file” and the “CSS file for RTL languages” as shown below.

rtlcss style.css style-rtl.cssDeveloping blocks is even easier. If you’re developing blocks according to a template, you’re probably building the source using @wordpress/scripts, which automatically generates CSS files for RTL languages. These CSS files are also automatically loaded according to the site’s locale.

There are no special considerations when using RTLCSS, but you should be aware of Control Directives. The most commonly used directive is the /*rtl:ignore*/ syntax, which prohibits automatic transformation of physical properties.

.test {

/* rtl:ignore */

left: 10px;

}Icon Direction

The most basic support for RTL languages is through CSS, and simply providing the appropriate styles using RTLCSS is sufficient, but one thing that is often overlooked is the “direction of images and icons.”

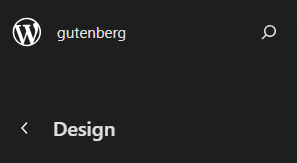

For example, let’s look at the links with chevron icons in the site editor.

If you invert the physics properties for an RTL language, the layout will look like this:

This icon’s direction is incorrect; it should semantically be facing right.

You could use CSS to rotate the icon 180 degrees only in RTL languages, but the approach commonly used in Gutenberg is to use the isRTL() function to detect the locale and load the opposite icon.

import { __, isRTL } from '@wordpress/i18n';

import { Button } from '@wordpress/components';

import { chevronLeft, chevronRight } from '@wordpress/icons';

function BackButton() {

return (

<Button icon={ isRTL() ? chevronRight : chevronLeft }>

{ __( 'Back', 'my-plugin' ) }

</Button>

);

}Form Elements

Despite being an RTL language, there are some contexts where you might want to force LTR. One example is email and url fields.

These fields generally expect only Latin characters to be entered, so apply direction: ltr. If you’re using the RTLCSS mentioned above, use a directive to prevent automatic transformation of this property:

input[type="email"],

input[type="url"] {

/* rtl:ignore */

direction: ltr;

}Additionally, for textarea elements, whether LTR should be enforced depends on the context: for example, in Gutenberg, LTR is enforced for textarea elements that expect code or HTML input.

Non-Latin characters

Non-Latin characters are writing systems other than the alphabet (A-Z), and Japanese is also a non-Latin character. In particular, problems are likely to occur in logic that assumes it is a Latin character.

Character Decoding

Here is an example of how improper character decoding can lead to unexpected results. For example, the following code implements logic to retrieve and display post slugs:

// ❌ Don't

import { useSelect } from '@wordpress/data';

export default function useSlugForDisplay() {

const slug = useSelect(

( select ) => select( 'core/editor' ).getEditedPostSlug(),

[]

);

return slug;

}This logic works fine if the post slug contains only Latin characters. But what if the slug contains a non-Latin character, such as “投稿“?

In the above hook, you’ll get the encoded string %e6%8a%95%e7%a8%bf, which is incorrect for display.

To solve this, you can use decodeURIComponent or its wrapper function safeDecodeURIComponent.

// ✅ Do

import { useSelect } from '@wordpress/data';

import { safeDecodeURIComponent } from '@wordpress/url';

export default function useSlugForDisplay() {

const slug = useSelect(

( select ) => select( 'core/editor' ).getEditedPostSlug(),

[]

);

return safeDecodeURIComponent( slug );

}Generate Slug Based on User Input

When generating a value internally based on user input, assuming only Latin characters, this may result in unintended behavior.

For example, in Gutenberg, the change-case library is used to pass user input values through the paramCase function to generate strings for slugs and presets. However, because the paramCase function removes non-Latin characters, there is a risk that the value will become empty.

console.log( paramCase( 'Hello World' ) );

// > 'hello-world'

console.log( paramCase( 'こんにちは世界' ) );

// > ''There are various approaches to solving this problem, but if we take a look at what has been done in Gutenberg in the past, we can consider the following approaches:

- Reject input of non-Latin characters in the first place.

- Use some kind of index number or random key instead of relying on user input.

- Use a fallback value if the value generated from user input is empty.

- Creating a new color in multibyte character, the style in editor will be broken. · Issue #39210 · WordPress/gutenberg

- Site Editor: Limit template part slugs to Latin chars by Mamaduka · Pull Request #38695 · WordPress/gutenberg

- Fix: save custom template with non-latin slug by t-hamano · Pull Request #69732 · WordPress/gutenberg

Layout and Design

Width of Element Changes

When text is translated, the size of elements containing that text may change depending on the locale, and text may wrap.

While it’s unrealistic to test all text in all locales, it’s important to try the following approaches in areas where problems are likely to occur, in order to prevent layout disruptions due to overflow or wrapping in advance.

- Don’t cram elements whose width may vary into a narrow container.

- Apply

overflow-x: autoto allow overflow. - Use flex layout to wrap overflowing elements.

- Apply

word-break:{break-all|break-word|auto-phrase}to prevent overflow. - Apply

text-overflow: ellipsisto hide the end of overflowing text with “…”. However, since this visually truncates the text, it may be best not to use it too often from an accessibility perspective.

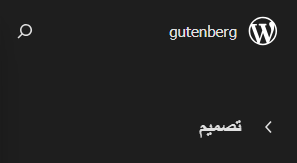

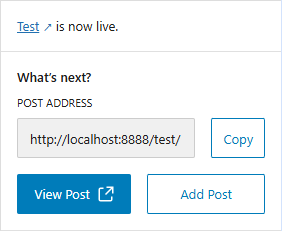

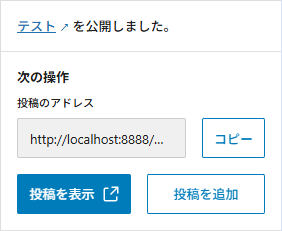

Just one real-world example in Gutenberg is the publish post panel: when you publish a post, a horizontal row of buttons appears in the sidebar. This layout works fine, at least in English and Japanese.

英語

日本語

However, in German (de_DE) the text for these buttons is long, so the buttons wrap to prevent overflow.

Date Order

The order of the year, month, and day varies by country.

- YMD: Japan, China, Korea, etc.

- MDY: Mainly the United States

- DMY: United Kingdom, France, Germany, etc.

For example, if the input fields for year, month, and day are separate and the order is hard-coded as shown below, it may feel unnatural in certain locales. How can we change this order depending on the locale?

<label for="year"><?php _e( 'Year', 'my-plugin' ); ?></label>

<input type="number" name="year" id="year" />

<label for="month"><?php _e( 'Month', 'my-plugin' ); ?></label>

<select name="month" id="month"></select>

<label for="day"><?php _e( 'Day', 'my-plugin' ); ?></label>

<select name="day" id="day"></select>WordPress core treats these individual form elements as placeholders for translation strings, allowing them to be reordered based on locale.

/* translators: 1: Month, 2: Day, 3: Year, 4: Hour, 5: Minute. */

printf( __( '%1$s %2$s, %3$s at %4$s:%5$s', 'my-plugin' ), $month, $day, $year, $hour, $minute );On the other hand, Gutenberg has the DateTimePicker component that is useful for entering dates. This component has the dateOrder prop, and the order of the year, month, and day will automatically change depending on its value. Therefore, if you use this component, you can deal with this issue by making the argument itself translatable.

import { DateTimePicker } from '@wordpress/components';

const MyDateTimePicker = ( date, onChange ) => {

return (

<DateTimePicker

currentDate={ date }

onChange={ onChange }

dateOrder={

/* translators: Order of day, month, and year. Available formats are 'dmy', 'mdy', and 'ymd'. */

_x( 'dmy', 'date order', 'my-plugin' )

}

/>

);

};

Leave a Reply